Aspiration after Globalization

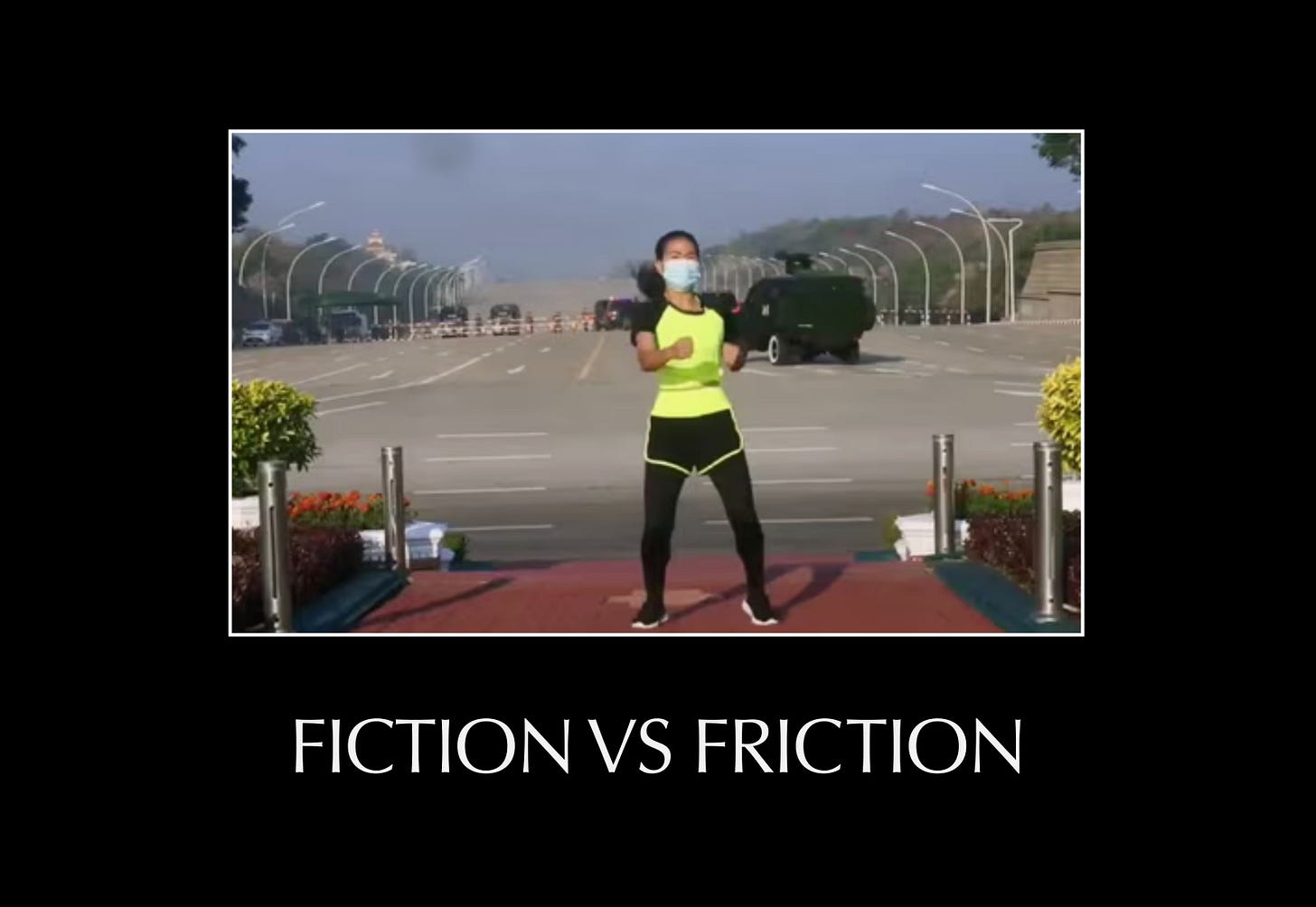

The mismatch between fiction and friction will be defining the era of Networked Realism

Supply chains are snapping, borders are closing, but the feed keeps refreshing. We belong to communities we’ll never visit, desire products we’ll never touch, and have our lives intimately intertwined with impersonal networks of people hidden all over the world.

This is part 5 of 6 of New World Order: a newsletter series on how macro shifts in politics, economics and global infrastructure affect culture.

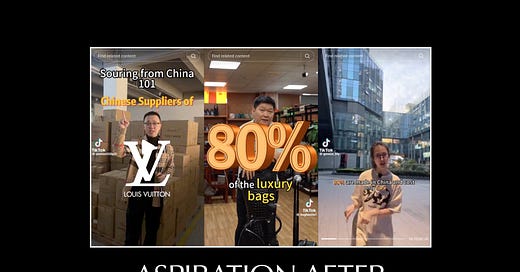

After the high water mark of last April's trade escalations between the US and China (and frankly the rest of the world), TikTok became flooded with testimonial videos from Chinese manufacturers hoping to expose US and EU luxury brands whose products they claimed to be making in their factories. They were then offering to sell the very same Lululemon leggings or Birkin bags at a fraction of the price that these brands were selling them, exposing the markup of expensive products while, simultaneously, demonstrating that Chinese manufacturing is not just for cheap goods, but also produces some of the most well-made and exclusive items available.

What made those TikToks from Chinese manufacturers draw attention wasn’t the supply chain drama or the geopolitical implications. It was that they were speaking directly to consumers not through press conferences or white papers, but to the feeds of teenagers in Texas and luxury resale enthusiasts in Berlin. Just a manufacturer in Guangdong province going viral for offering the truth (whether or not it was actually true) behind the labels to millions of people scattered across the world with an interest in luxury production, or the controversy–without any interjection from the brands themselves.

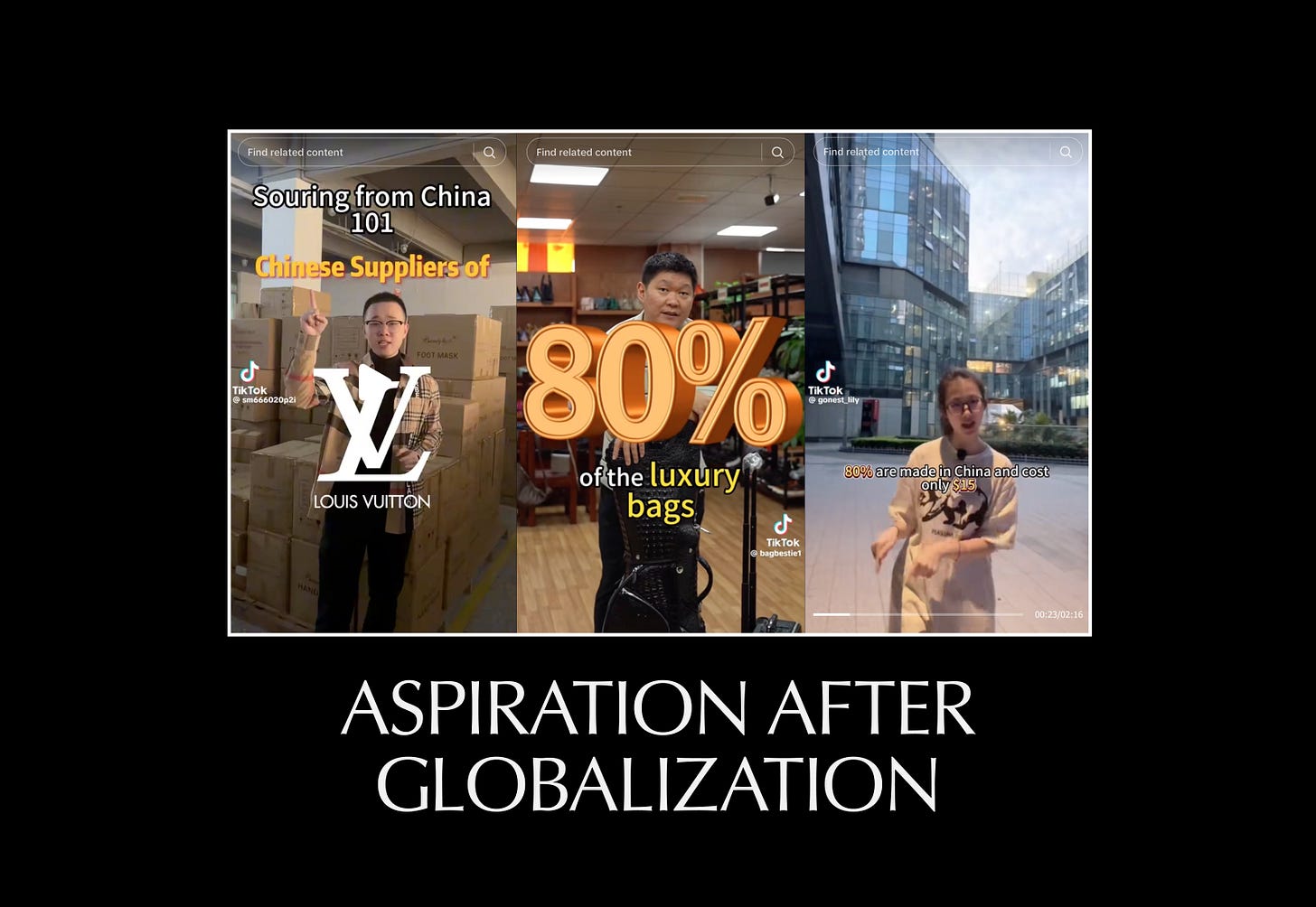

That’s the shape of the world now. Not flat. Not global. But both fragmented and deeply connected only in increasingly orthogonal ways that no longer fit on the map of nations, towns, or regions that we were formerly tied to.

We usually think of Globalization in terms of easily accessible consumer goods, available through the likes of Amazon or Shein, that democratized consumerism, offering global masses of people the feeling of abundance by way of advanced global logistics chains that moved “just-in-time” ever so seamlessly. A certain aspirational idea of the “good life” (overindexed on middle class American values) or even “progress” globally was articulated by the abundance it gave access to.

But global production was only half the story. As media and informational networks scaled to match the breadth of global production, industry then had to scale up to match the speed of informational networks. Both congealed into what we call Networked Realism, where it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is the end of networked information and production.

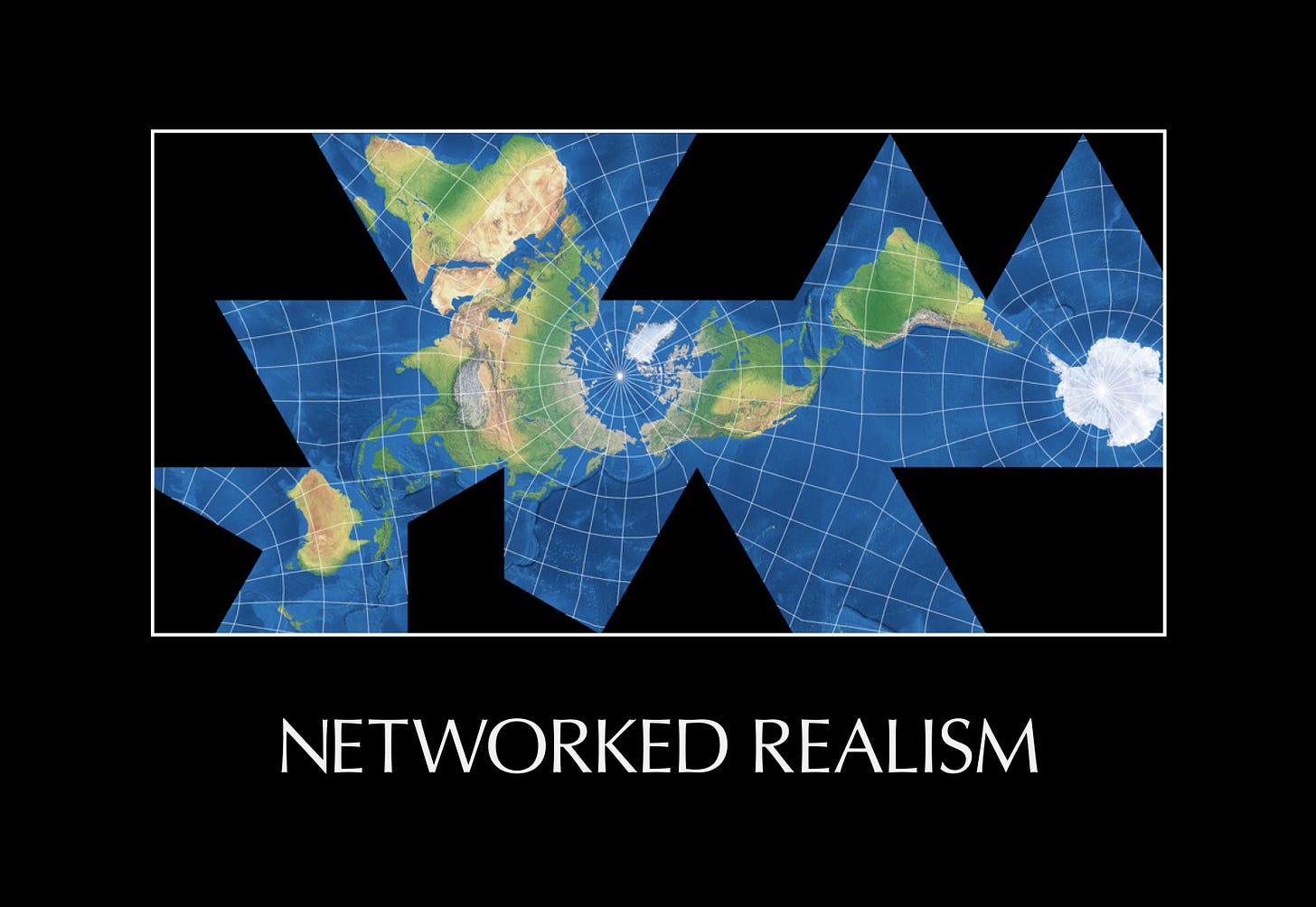

Once digital media and the production of physical goods converged in scale and speed, they began reshaping consumer culture in irreversible ways. The internet stopped connecting people who have or will know each other offline, like “social” media had. Instead it evolved into a space for platforms and intermediaries to shepherd potential audiences toward para-social interests with brands, fandoms, small communities, ideologies and hobby interests through network effects of attention.

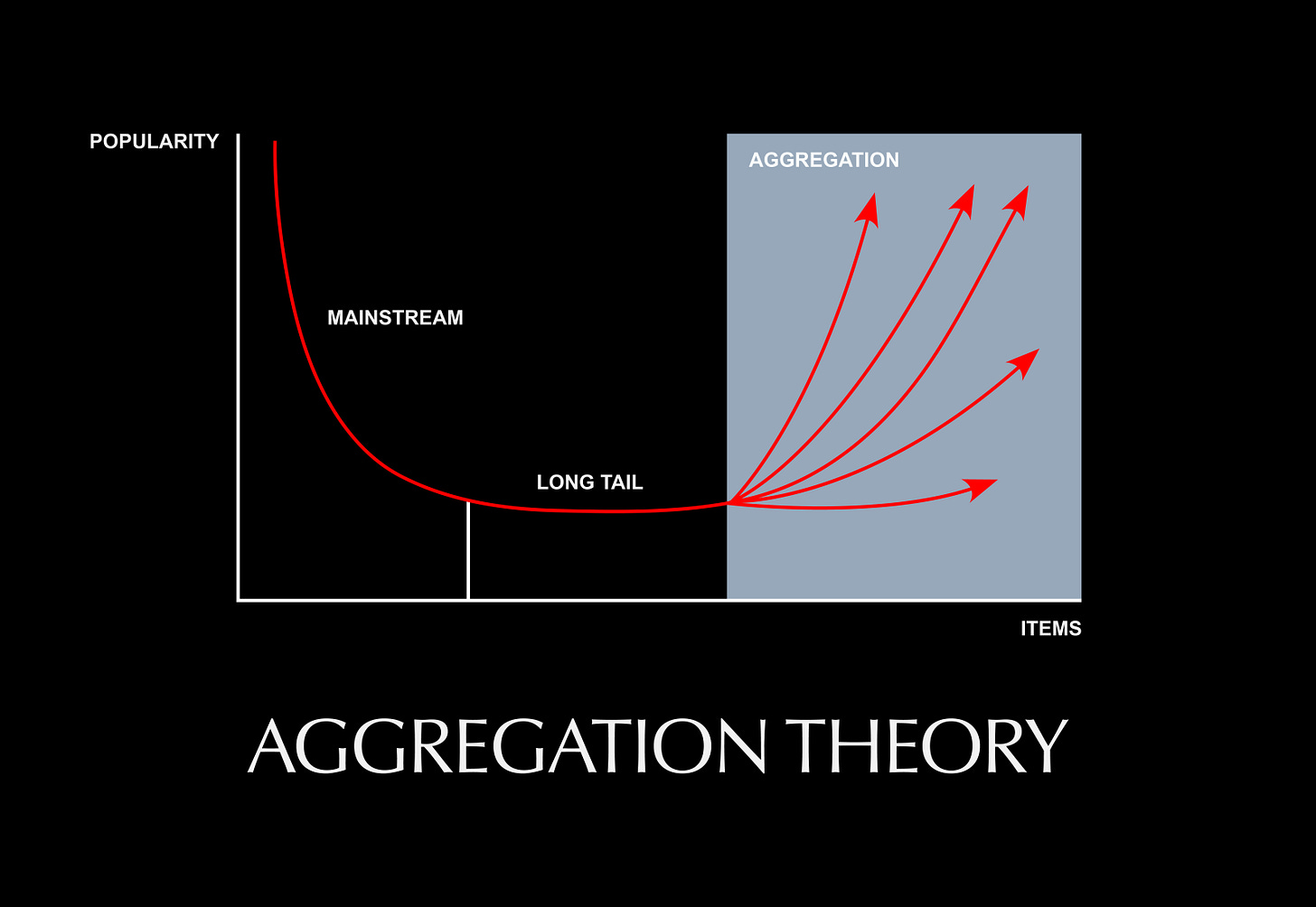

Selective algorithms and commercial incentives became major drivers in the information space; and our lives began reflecting the proliferation of niche aesthetic D2C products that could be produced just-in-time. Each of those niche aesthetics or products were only able to be so niche because of the ability of networks to aggregate information and logistics at-scale.

You might be in a Lagos apartment, dreaming in the aesthetic grammar of the cult of Tokyo streetwear. Or living in a rural town in Arkansas, emotionally tethered to a techno scene in Kyiv you’ll never visit. You might live in São Paulo, but your tightest community is a Discord server run by a Malaysian fashion archivist who shares bootlegs of unreleased runway collections. Or maybe you’re a Somali gamer in Sweden whose entire social life takes place inside a modded map in Fortnite.

Whole economies of scale for niche styles, for large mutli-player games, for D2C products, or crypto degen communities could economically and culturally thrive with the help of individuals scattered across the globe, propelled by long tail business models and the platformization of everything. Relationships and communities began forming which were entirely different from the localized versions that occurred in the past because they more closely resembled communities of people who share a higher idea like a religious group, a cult, or a nation even. Fandom became a totem and an aggregator amidst a sea of niche trajectories.

For any product or ideology, or aesthetic to succeed in this new paradigm, or to reach the prominence of a mass consumption equivalent, it would need to aggregate different, loosely affiliated groups of people into audiences or groups that might be large enough to have impact. Otherwise, no single niche group can move the needle.

This is why the most impactful ideas or subcultures today are not those with the most average appeal overall, but with the broadest buy-in from different groups of people. We moved from the statistical average (something in the middle), to the statistical mode (the most often occurring) culture.

Now all of this would be fun if the infrastructure that made it possible wouldn’t be crumbling before our eyes.

Geopolitical tensions, the end of the liberal political era, trade wars, and deeply volatile volleys in global markets are daily news, rising inflation, rolling black-outs over whole regions (cite), insurance companies pulling out of climate ravaged cities (cite), deadly airport infrastructure fails (cite), goods or services “not available in your region,” TikToks of starving children in Gaza wedged between shampoo ads and brain rot, or a trip to the US overshadowed by fears of detention (cite).

It becomes painfully clear that the aspirational promises of Globalization are no longer matching the promise of abundance, creating a strange frictional backdrop to the frictionless reach of our lives online. And what’s weirder still is that we experience this friction alongside people we share IRL space with (i.e. the people waiting for the same delayed flight as you do) but have less and less shared worldviews with as our minds are trained by different, often competing, narratives.

Over the next ten years we see the mismatch between fiction (what we believe online) and friction (what’s happening IRL) as the key driving tension as the era of Globalization cedes to the era of multipolar Networked Realism.

Localities saw shared values get fragmented into millions of niches that only made sense because of the density of access made possibly globally, in aggregate, and drove a wedge between neighbors, creating a loneliness epidemic; Cultural difference got flattened into consumer groups; whole regions collapsed into poverty while others were immiserated by cost of living crises born out of overtourism.

While information flows freely, frictionless, across networks to an archipelago of people you share interests with online, the IRL world doubles down on barriers between nations, regions, through infrastructure, and on belonging only on lines of nation, locality, and values that have little to do with the actual communities people feel attached to because of the networks they are part of.

Other than a few good memes, most of us are asking ourselves what it is we value and actually want out of this global project.